Attention Readers!

We have not stopped writing in this blog! We have a lot of new stuff coming up in the next few weeks, so please subscribe to us or keep checking back regularly!

Thanks,

Heather & Alex, 1/1/11

Kale

“Life expectancy would grow by leaps and bounds if green vegetables smelled as good as bacon.”

-Doug Larson

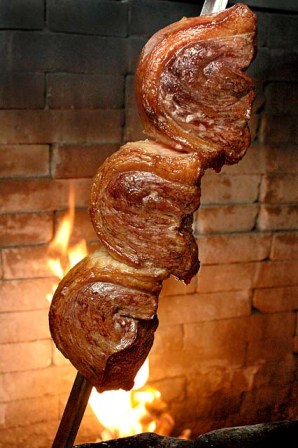

Admittedly, I was one of those stupid bratty children who threw fits every time a green vegetable was on my dinner plate. I was the quintessential picky eater. Green beans? Yeah, forget it… pass the cinnamon applesauce. To this day, I’m pretty sure my mom is still in disbelief that I ended up pursuing culinary arts as a profession. Somewhere along the way though, green vegetables stopped being so horrible (probably around the time my mom stopped buying canned vegetables 🙂 ) and I actually started to like them. Leafy greens, however, were something I hadn’t acquired a taste for until pretty recently. I never really cared for collared greens while living in New Orleans, and would avoid the whole braised greens family whenever they appeared in dishes we made at school. To be quite honest, I didn’t like kale until the day we arrived in São Paulo and had feijoada for lunch. You know what they say, though – bacon makes everything better.

Kale is a form of either green or purple cabbage that is unique because it doesn’t form a head when it grows – it grows in clusters of large leaves, which can be either flat or curly at the edges. The season for kale is between mid-winter and early spring where it can be found in abundance in most produce sections of the local grocery store. However, you can find kale year round. It grows most abundantly in central/northern Europe and North America – it prefers cooler climates, but does grow in more tropical regions as well. Kale can tolerate almost any type of soil as long as it drains well.

Until the end of the Middle Ages, kale was one of the most common green vegetables in all of Europe, and was brought to the USA during the 17th century by English settlers (and to Brazil by Portuguese settlers; it’s called couve here). During World War II, the cultivation of kale in the U.K. was encouraged by the Dig for Victory campaign. The vegetable was easy to grow and provided important nutrients to supplement those missing from a normal diet because of rationing. It faded from the meal table and recipe books after the war, probably because of its somewhat metallic taste and the fact that it turned into an unappealing green mush when boiled. Thankfully, modern cooking has figured out how to preserve the color and flavor of kale, and the wartime food is slowly making a comeback.

Health Benefits

Kale, like all dark, leafy greens, is also really, really good for you. Kale is considered to be a highly nutritious vegetable with powerful antioxidant properties; it’s considered to be anti-inflammatory. Kale is very high in beta carotene, vitamin K, vitamin C, lutein, zeaxanthin, and reasonably rich in calcium. Kale has seven times the beta-carotene of broccoli and ten times more lutein. Kale is rich in vitamin C, not to mention the much-needed fiber so lacking in the daily diet of processed food eating Americans.

Like broccoli and other dark greens, kale contains sulforaphane, a chemical believed to have potent anti-cancer properties. Science has discovered that sulforaphane helps boost the body’s detoxification enzymes, possibly by altering gene expression. This in turn is purported to help clear carcinogenic substances in a timely manner. Sulforaphane is formed when cruciferous vegetables like kale are chopped or chewed. This somehow triggers the liver to produce enzymes that detoxify cancer-causing chemicals (which we all are exposed on a daily basis), inhibit chemically-induced breast cancers in animal studies, and cause colon cancer cells to commit suicide. (source) The same website also suggests that smokers can reduce their risk of developing emphysema or lung cancer by increasing their vitamin A consumption – not advocating smoking, of course, just trying to help out those who can’t quit.

How to make kale taste good

At DOM, I’ve been assigned kale fabrication as one of my duties this week. I wanted to include a step-by-step fabrication guide for this blog to encourage everyone to give kale a chance – it’s really not half bad 🙂

———————————————————–

Step one: Wash all the leaves VERY well. Kale contains a good amount of sand when raw, so make sure you rinse the whole leaf. Don’t use any leaves that are starting to yellow – kale yellows as it gets older, and the older it gets, the more bitter it becomes. Use fresh, young leaves with as few insect bites as possible.

Lay the leaves on top of each other – work with about 5-8 at a time, depending on their size. Line up the stems evenly.

Step two: With a sharp knife, cut the leaves directly parallel on one side of the stem, separating the stem from all the leaves.

Step three: Repeat step two on the other side of the stem – remove the stem completely and separate the two halves.

Step four: lay both sides of the leaves on top of each other. Put the largest leaf on the bottom, and make the bottom leaf about 2″ longer on top than the rest of the pile.

Step 5: Tightly roll the pile into a cylinder.

Step 6: Tie a rubber band around the bundle of kale. Trim the bottom so it’s even. Slice the bundle in very thin strips (julienne is ideal). Slicing the kale on a deli slicer makes it super easy – if you don’t have a slicer, a mandolin would work too. If you don’t have a mandolin, a knife will do just fine. 🙂

Next, blanch the shredded kale in boiling, salted water for 3-5 minutes. Don’t overcook it! Remove and immediately shock it by submerging in ice water. This preserves the bright green color of the kale, as well as the snappy texture.

While the kale is cooling down, dice up a few strips of bacon – one per portion should be enough. In a saute pan, cook the bacon over medium heat until it renders its fat and gets crispy. Add some minced garlic and cook just until you can smell it.

Drain the kale and add it to the saute pan with the bacon (and its fat). On medium-high heat, sauté everything together just until the kale gets hot. Season with salt and pepper, and serve as a delicious, nutritious side dish.

If you have a favorite way to eat kale, please share in our comments!

Maxixe

“An onion can make people cry, but there has never been a vegetable invented to make them laugh.”

-Will Rogers (1879-1935)

During our first few weeks here, we visited a lot of local markets (no, really – a LOT). Almost everything was unfamiliar to me, but certain products stood out in my mind because of the way they looked – for their sheer uniqueness. I remember seeing this one in particular at almost every market:

and every time I wondered “What the heck is that thing?” I mean, really, to a Westerner, this looked like some sort of green mutant weapon, not a vegetable or a fruit. I was always too uneasy about its appearance to try it – something about the egg-shaped koosh ball with a tail just… didn’t look appetizing.

Luckily, one of my first tasks at DOM was to learn how to fabricate these little oddities, known as Maxixe (pronounced mah-SHE-shee). Maxixe is, of all things… a type of cucumber. Yeah, I was way off. They’re prickly, but not thorny – the spikes are more like rubber than rose bushes, and the small hairs on the long, curly stem are only slightly odd feeling. To eat these little guys, first trim off the tail and any nub that might be on the bottom end. With the side of a knife, gently scrape the spikes off (this took me at least 3-4 tries before I stopped mangling the skin – use very gentle pressure and keep the knife slightly angled upward) and rinse in cool water… and that’s it. Scraping the spikes off helps to preserve the color, flavor, and texture of the skin – but if you’re totally weirded out by the spikes, you can peel it completely. Maxixe can be eaten raw, but they are filled with seeds – so most people prefer them cooked. At DOM, the cleaned maxixe we prepare is diced and added to a ratatouille-style preparation used in Alex Atala’s other restaurant, Dalva e Dito (which is just down the street from DOM).

When I started my research on maxixe, the first dozen or so pages that came up were all related to a type of dance – apparently, Maxixe is the name of a Brazilian traditional dance that’s sometimes called the “Brazilian Tango”, an Afro-Brazilian dance developed by black Chopi slaves from… Maxixe, Mozambique.

Our little green edible koosh-balls most likely originated in Africa. At one point, they were thought to have originated from the West Indies – which is why sometimes you can find them labeled as “West Indian Gherkins.” Other places also call maxixe “Burr Cucumber”. I say ignore the labels – you’ll know it if you see it! Maxixe is popular in Northeastern Brazilian cuisine, where they have a stew called “Maxixada” ( recipe follows). Maxixe is also eaten raw in salads, pickled, boiled, or lightly sauteed. It tastes slightly sweet with just a little hint of bitter – I think they’d be great in the Greek Tzatziki sauce. As an added plus, they’re very low in calories and high in zinc.

I also found a website run by a group of students from the University of Massachusetts who specialize in growing “specialty” produce like this – they sell to local farmers markets in the Boston and Lancaster area. I couldn’t find information about finding maxixe anywhere else in the US, but this website sells the seeds for export if you’re feeling adventurous 🙂

Hot and Spicy Brazilian Maxixada

This dish is eaten over rice or a mixture of rice and beans. Traditionally, it’s cooked with dende oil (red palm oil), but you can substitute olive oil if you can’t find dende.

1/4 cup dende palm oil ( or olive oil )

2 cups onion, minced

1 pound young, tender maxixe

1 chayote, diced (peeled zucchini can serve as a substitute)

1 tbsp garlic, minced

2 cups tomato, chopped

8 ounces picked cooked crab meat

1 cup coconut milk

2 or 3 tbsp chopped cilantro, or to taste

Zest of half a lime

Salt and freshly chopped or ground hot pepper to taste (preferably malagueta)

Optional garnish: 4 boiled crabs cut in half

Heat oil in a large sauté pan or skillet and add onion, maxixe, and chayote or zucchini. Cover and cook 6 minutes over medium heat, then add garlic, tomato, picked crab and coconut milk. Stir and cook uncovered until the tomato is reduced and the sauce turns light orange (about 8 minutes). Add cilantro and lime zest, then season to taste with salt and hot pepper. Once the liquids are well combined and hot (about 5 minutes), serve over rice with hot boiled crabs as a garnish. Serves 4 to 6.

( recipe taken from here – the article preceding the recipe is really useful for planting and harvesting tips)

Pirarucu

While working at D.O.M. we have been exposed to many ingredients that Chef Alex Atala discovered on his research travels through Brazil. Pirarucu is a fresh water fish that has been consumed for centuries by the people of the Amazon. Historians affirm that the species dates back to the Jurassic Period (200 million years back), which makes it one of the most ancient fish species around It is also one of the biggest scaly fishes in the world, and the biggest fresh water fish in the world. Since they are so hard (and large), the scales from pirarucu are used as nail files and also employed in crafts to make jewelry and souvenirs. In other areas it can also be called arapaima or paiche.

An Amazonian Legend:

The name pirarucu is derived from two indigenous terms: pira which means fish, and urucum which means red (the color of the fish´s tail). In native lore there is the legend of Pirarucu, a young Indian who belonged to the Uaiá tribe from the Southwest plains of the Amazon. Pirarucu was a brave warrior but he had an evil heart; he was selfish and excessively proud of his powers. He loved to criticize the gods and to abuse his status as the chief’s son. Tupã, the God of gods, had been observing him and decided to punish him. Tupã called out for the gods Polo and Iururaruaçú to punish the tribe with storm and lightning. The young Pirarucu laughed and despised the God’s wrath. Tupã then called upon Xandoré, the god who hates humans, to strike Pirarucu and drag him to the depths of the river where he was turned into a big dark fish. Pirarucu now swims through the waters where he terrorizes the other fish and even other small animals.

Pirarucu is a prized fish that has been a victim of predatory fishing in the Amazon. This fish species is very particular because it lives in calm waters where the oxygen level is low, so to compensate, it developed a respiratory system that allows it to breathe air from the surface (in addition to using gills for capturing oxygen from the water). The fish can grow as big as nine feet long and can reach weights over 450lbs. Because of its unique breathing characteristics, the fish is an easy prey for hunters who will harpoon it when it surfaces for air (they usually have to surface about every fifteen minutes). The fish also develops reproductive maturity later in life. For these reasons the governments of Brazil, Peru, and Colombia have put restrictions to the specific seasons and areas where the fish may be caught. Pirarucu is one of 21 Brazilian resources listed on Slow Food’s Ark of Taste. Since its rise in popularity with fine dining restaurants, pirarucu farms have become a successful and sustainable business. Because the fish lives in low oxygen areas, it adapts well to captivity in ponds. Farmers in São Paulo state can supply the restaurant demand in the city, guaranteeing fresh fish delivered the day it is removed from the ponds. And, for anyone wanting to start a fish farm in Brazil, there are several websites where you can mail order pirarucu fry (or babies).

Mail order pirarucu

D.O.M.’s menu has a pirarucu that is sauteed and served with sagu of açaí and red wine (remember the garnish that Heather was assigned to prepare everyday this week?), and a tucupi with herbs sauce (tucupi is a broth made from the water removed during the process to make manioc flour which is cooked for hours to remove the toxins).

D.O.M.'s pirarucu (photo by Giacomo Bocchio)

Widely used in the cuisines of the Amazon region, Pirarucu is consumed fresh or preserved in salt – it even has the nickname bacalhau da Amazonia (Cod of the Amazon). There are many recipes that traditionally came from Portuguese cuisine where salted cod is widely used and now are common to the Amazon cities with the presence of salted pirarucu (fried pirarucu cake is the main example). Another traditional recipe in the region is Pirarucu de Casaca, a layered casserole that usually includes salted pirarucu, manioc flour, onions, bananas, potatoes, and olive oil.

One interesting recipe I read in a book about the Amazon is called Pavulagem (this word loosely translates into English as boasting, but in the north of Brazil it has many more connotations which would require a professional linguist to explain). 🙂

Pavulagem

8 portions

(This dish can also be prepared with other white, firm-flesh fishes such as dourado or fresh cod).

- 4 tablespoons olive oil

- 1 onion, minced

- 2 garlic cloves, minced

- 3 tablespoons parsley, chopped

- 1 cup butter

- 4 cups manioc flour

- 10 eggs

- salt and pepper to taste

In a skillet, heat the olive oil and sauté the onion and garlic until they start to brown. Add the parsley and 3/4 of the butter. When the butter melts add the manioc flour, keep stirring until the flour is browned. Reserve. With the remaining butter cook the eggs, scrambled, until done but still soft. Mix with the manioc flour and reserve.

- 1 lime, quartered

- 4 cups cold water

- 2 cloves garlic, chopped

- 2 tablespoons olive oil

- salt and pepper to taste

- 1 lb. fresh pirarucu fillets, cubed

- 3 eggs

- juice of 1/2 a lime

- 3/4 cup water

- 1 cup flour

- 1 cup breadcrumbs

- 3 cups oil (for frying)

- 6 oz Brazil nuts, grated

In a blender, pulse the lime with the water and then strain. Blend again, adding the garlic, olive oil, salt, and pepper. Marinate the fish in this liquid for 20 minutes. Beat the eggs and combine with the reserved lime juice and water. Drench the fish in this mixture and then dip it in the flour. Dip it again in the egg mixture and lastly in the breadcrumbs. Deep fry the fish and after it is drained serve it with the cooked manioc flour (farofa). Sprinkle the Brazil nuts on top.

Manioc

Today I just ate manioc with salt, and tomorrow I don’t know what I’ll do.

~ Maria Gonzalez

Manioc, also known as yuca or cassava in Central America and the U.S., is a white starchy tuber with a delicate taste. It has been a staple of the Brazilian Indians’ diet for centuries. In Tupi, the native language, manioc is called mandioca in Southern Brazil, macaxeira in northeastern Brazil, and aipim in Rio de Janeiro; it’s called tapioca when referring to its starch. Manioc is native to west-central Brazil, and evidence shows that it was domesticated over 10,000 years ago. A volcanic eruption that buried a Mayan village 1,400 years ago preserved a manioc field – the first evidence that the crop was cultivated by the ancient people, and the first evidence of new-world cultivation.

Manioc was so important to ancient civilizations that it often appeared in art sculptures

Manioc is a perennial woody shrub with an edible root, which grows in tropical and subtropical areas of the world. It has the ability to grow on marginal lands where grains and other crops do not grow well; it can tolerate drought and can grow in low-nutrient soils. Because manioc roots can be stored in the ground for up to 24 months (some varieties for up to 36 months) harvest may be delayed until market, processing, or other conditions are favorable – a definite plus for low-income farmers. In Africa and Latin America, manioc is mostly used for human consumption, while in Asia and parts of Latin America it is also used commercially for the production of animal feed and starch-based products. In Africa, manioc provides a basic daily source of dietary energy. Roots are processed into a wide variety of pastes and flours, or consumed freshly boiled. In most of the manioc -growing countries in Africa, the leaves are also consumed as a green vegetable, which provides protein and vitamins A and B. In Southeast Asia, manioc starch is used as a binding agent, in the production of paper and textiles, and, what I found most interesting, as monosodium glutamate – the controversial flavoring agent in Asian cooking. In Africa, manioc is beginning to be used in partial substitution for wheat flour.

This website has a really interesting list of the many different uses manioc can have after processing.

The manioc root is long and tapered, much like a domestic sweet potato. The skin is a dark brown, almost like tree bark, and outside of the immediate growing region it will always be coated in wax, due to its highly perishable nature. The flesh is firmer than a potato, very starchy and white, and a woody ribbon runs along the axis – it’s helpful to find and remove this before cooking or serving. Store whole manioc as you would potatoes, in a cool, dark, dry place for up to one week. Peeled manioc can be covered with water and refrigerated or wrapped tightly and frozen for several months.

Toxicity

Manioc is classified as either “sweet” or “bitter” depending on the level of toxic cyanogenic glucosides. The “sweet” (actually “not bitter”) varieties can produce as little as 20 milligrams of cyanide per kilogram of fresh roots, whereas “bitter” ones may produce more than 50 times as much (1 g/kg). Manioc grown during drought are especially high in these toxins. A dose 40 mg of pure manioc cyanogenic glucoside is enough to kill a cow. It can also cause severe calcific pancreatitis in humans, leading to chronic pancreatitis. Improper preparation of bitter manioc most commonly causes a disease called konzo (which means “bound legs” in Yaka), an epidemic paralytic neurological disease which causes permanent disability, but doesn’t progress at all. Nevertheless, farmers often prefer the bitter varieties because they deter pests, animals, and thieves. The poisons are destroyed by soaking in water and by heat during cooking – manioc should never be eaten raw. A safe processing method used by the pre-Columbian indigenous people of the Americas is to mix the cassava flour with water into a thick paste and then let it stand in the shade for five hours in a thin layer spread over a basket. In that time about 5/6 of the cyanogenic glycosides are broken down by the linamarase; the resulting hydrogen cyanide escapes to the atmosphere, making the flour safe for consumption the same evening.In my opinion, it’s amazing that the native Indians figured out that manioc was even edible at all!

The traditional method used in West Africa is to peel the roots and put them into water for 3 days to ferment. The roots then are dried or cooked. In Nigeria and several other west African countries, they are usually grated and lightly fried in palm oil to preserve them. The result is a product called ‘Gari’. Fermentation is also used in other places such as Indonesia. The fermentation process also reduces the level of antinutrients, making it a more nutritious food.

Culinary Uses

Manioc is the third largest source of carbohydrate energy in the world – here in Brazil, you see manioc everywhere. Much like the potato, the culinary possibilities of the manioc seem infinite. Manioc can easily be substituted for potatoes in soups and stews. It can be boiled and mashed, and it doesn’t need as much butter or salt as mashed potatoes often do. At DOM, the nighttime interns make about 10 gallons of manioc puree per day.

Fried Manioc wedges

My favorite way to eat manioc is definitely fried. I think it’s a thousand times better than french fries. Fried manioc is super crunchy on the outside, and soft and flaky on the inside – I think it’s actually better without a dipping sauce. To make fried manioc, simply boil the peeled roots until they are “fork tender”. Cut into 2″ rounds and separate into sticks with a fork or knife. deep-fry in very hot oil until they are golden brown and crispy; sprinkle with salt and enjoy. In our brief introduction to South American cuisine at the CIA, we made manioc chips – the exact same process as potato chips (peel, slice thinly on a mandolin, fry).

Boba pearls, used in the popular Bubble Tea drink, are made from tapioca starch. At DOM, I’ve had the “sagu” duty all week – cooking tapioca pearls with açaí and red wine.Most people are also familiar with tapioca pudding – tapioca pearls cooked with milk, sugar, and egg, chilled and eaten as a dessert. Tapioca starch can also be used in gluten-free baking (remember pão de queijo?).

Farofa

Of course, no meal here in Brazil is complete without farofa, which I’ve mentioned several times already – the coarsely ground manioc flour that’s sprinkled on just about every dish here. It’s taken me a little while to get used to it, but I now actually kind of like it – the crunchiness that comes from dipping a piece of rare meat into a pile of farofa isn’t all that bad.

What’s your favorite way to eat manioc??

Mocotó

“Great restaurants are, of course, nothing but mouth-brothels. There is no point in going to them if one intends to keep one’s belt buckled.”

-Frederic Raphael, (1931- ) British author

Mocotó Restaurante & Cachaçaria

After finishing our Saturday morning deep-clean of the D.O.M. kitchen, we drove over an hour from Jardins to Vila Medeiros, a very lower-middle class working neighborhood at the very northernmost edge of the city, marking the municipal end of São Paulo and the beginning of a large favela (a very poor neighborhood; a slum). It was Alex’s mom’s last weekend in town, and we all wanted to have one last great meal together. Alex and his brother picked Mocotó based on reviews in various local papers and outstanding recommendations from several of their friends.

Mocotó is, in essence, a gastropub – it’s a bar that serves food. The main wall of Mocotó is nearly wallpapered floor-to-ceiling with framed news articles, press releases, reviews, and awards in at least 5-6 different languages, from the local papers to the New York Times. The bar is a renowned Cachaçeria, serving over 500 types of cachaça (the fire water sugarcane liquor that’s the national drink of Brazil) – the largest in the city, if not the country. The cachaça list gives you the name, region, and tasting notes of every cachaça they offer – it’s better than most wine lists in fine-dining restaurants. They even offer a cachaça club – you can buy an entire bottle of cachaça, write your name on it, and keep it at the bar for future visits. The restaurant, from the tables and chairs to the signs on the wall, is decorated almost entirely in carved wood – it’s a really relaxing, homey atmosphere. There are two main dining rooms, a terrace, and a small courtyard. We were told that we had to arrive by 11AM to get a table since they don’t take reservations… we were there a little after and were surprised to see the street corner so empty. However, by 11:30, at least 50 people had gathered outside the restaurant, and by the time the restaurant opened for service at noon, the line was wrapped around the block.

History

Mocotó specializes in Northeastern cuisine of Pernambuco, which is known for its distinctively unique culinary traditions – much in the same way New Orleans cuisine is viewed in the US. Mocotó was opened by Jose Olveira de Almeida in 1974, who moved from his farm in Pernambuco to São Paulo in the early 1960’s. At first, it was just a typical bar catering to the community of Nordestinos in Vila Medeiros – they sold booze, a few regional products like carne de sol (sun-dried meat) and rapadura (crystallized sugarcane), and their family recipe of mocotó. Mocotó is a very traditional tripe-and-calve’s foot soup flavored with tomatoes and the popular, super-spicy Malagueta pepper. The soup became the staple of the bar, and became increasingly popular with the locals who needed a bit of sobriety before heading home.

Jose’s son Rodrigo grew up helping in the restaurant. He had always wanted his father to expand the menu, but Jose never did. Rodrigo renovated the restaurant in secret one day while his father was away on a trip to Pernambuco, and soon afterward dropped out of environmental management school to study culinary arts. After formal culinary training, he spent the next few years traveling all over Brazil learning about regional cuisines, foods, and cachaças. Chef Rodrigo is known for lightening the high-protein, high-carb heartiness of Northeastern cuisine while allowing it to retain its wholesome flavors and aromas. Even though Rodrigo (now only 28 years old!!) is the main person in charge today, his father still comes in to season the mocotó and a few other dishes, just so they retain their authenticity.

The Meal

We started our lunch with a variety of cocktails – Alex ordered a “Garapa Doida” (a crazy sugarcane) made with cachaça, sugarcane syrup, pineapple juice, and a splash of fresh lime, and I ordered a drink called “Leite de Onça” (milk of the tiger) made with cachaça, condensed milk, honey, guaraná powder, and cinnamon – it was like a cachaça milkshake heaven (though, I think it would have been better paired with dessert – haha). There was also a passionfruit caipirinha, a frozen cajá and cachaça cocktail, and a “Pinga Colada” (pinga is another term for cachaça) made with cachaça, pineapple juice, coconut milk, and condensed milk – not to mention the dozens we didn’t try.

We started with two appetizers : carne de sol and torresminhos.

Carne-de-Sol with roasted garlic, manioc chips, and biquinho peppers *

- Carne-de-sol is the northeastern sun-dried meat, served on a hot griddle covered with “manteiga de garrafa” (a special type of Northeastern bottled butter) with caramelized onions, small mild biquinho peppers, manioc chips, and whole roasted garlic cloves. The flavor of the meat is incredibly rich and concentrated, and it’s unbelievably tender despite being cooked through.

- Torresminhos are the Brazilian version of chicharrones – basically, deep-fried cubes of bacon served with lime wedges. These…are a fat kid’s dream snack. I could have devoured 4 orders worth if my arteries would have stopped screaming at me :p Sadly, you probably won’t find torresminhos this delicious anywhere else – Mocotó uses sous-vide to achieve an incredibly flawless, melt-in-your-mouth (yet still crunchy) texture, complimented perfectly by the acidity of the fresh lime.

- Carne de Sol Bruschetta – we ordered this after our entreés, and it’s definitely among some of the best bruschetta I have ever had. Buttery cubes of carne-de-sol, cubes of fresh queijo coalho, tomatoes, and herbs piled on top of a fresh baguette and then gratinéed to give that delicious browned cheese flavor… it was our breaking point. Our stomachs almost burst J

For our entreés, we ordered everything to share with the table.

Tapioca de carne-seca

- Tapioca (manioc starch) pancake filled with fresh cheese, fried manioc, green onions, and aged beef – It figures that the one I chose was my least favorite, haha. It arrived at least 15 minutes before the rest of the food, so the wait probably caused some of the dryness and chewiness I tasted (though I was told it’s supposed to be chewy).

Escondidinho de carne-seca *

- Escondidinho de carne-seca : this was easily my favorite. Escondidinho is a simple preparation that basically puts meat – carne-seca [dried beef] or shredded goat – on the bottom of a ramekin, covers it with creamy manioc puree and requeijão, then tops it with fresh queijo coalho and browns it in the oven. The result is something that looks like a soufflé, but tastes better than any meat-and-potatoes dish you’ve ever had.

- Atolado de Bode – baby goat rib stew marinated in cachaça and apple vinegar, braised in butter, browned in the oven, and served with boiled manioc, baby tomatoes, pearl onions, olives, and mild green peppers. Super tender, super rich, and super delicious.

- Mocofava – this is essentially mocotó – the tripe and cow’s foot soup – with fava beans. It’s Rodrigo’s take on his family’s recipe – the favas make it creamier than the original version. To be honest, I had NO IDEA what was in this soup when I tried it, and it was delicious. I don’t particularly care for tripe, but it melted in your mouth. The seasoning was perfect and the texture wasn’t unpleasant at all, even though there were strips of tender, gelatinous meat in the broth.

Baião-de-Dois (from Mocotó's site)

- Baião-de-Dois – this is the Northeastern version of rice and beans, with cheese and meats in the mix. I had admittedly been getting tired of rice and beans (it’s served with almost every meal every day – and we’ve had it for lunch every day at DOM), but this was delicious. Instead of making a sauce with the beans and serving it over the rice, the beans are completely drained and mixed in with the rice and fresh cheese and meat. It’s a totally different flavor, and – in my opinion – not nearly as heavy.

We ended our lunch stuffed and happy – but, of course, someone always wants dessert, so we ordered two:

- Rapadura ice cream- Alex’s sister-in-law was adamant about her hatred of rapadura – she said it’s always “too sweet and too hard” (rapadura is dried sugarcane juice) – however, after everyone at the table raved about the ice cream, she tasted it and liked it so much that she ordered an entire portion for herself J It was honestly one of the best ice creams I’ve ever had. It was a deliciously rich cream base studded with little cubes of softened rapadura, topped with Catuaba liqueur – which is traditionally used in folk medicines as an aphrodisiac.

- Chocolate mousse with cachaça – The first thing I thought when I tried a bite of the mousse was “my mom would be in heaven right now.” Light, creamy, with a little kick from the cachaça – any chocolate lover would agree that it’s… damn good. There’s not much else I can say.

I’m not sure how we made it home, because I fell into a food coma and slept for 90% of the drive – and then for three hours afterward. I can easily say that lunch at Mocotó was the best meal I’ve had in Brazil so far, and one of the best I’ve had in a while. If you’re ever in São Paulo, I highly recommend that you pay the restaurant a visit (as an added plus, with the conversion rate, it’s really inexpensive when you pay in dollars or euros – drinks are about $3 and entrees about $10-$15) . Check out the website here: Mocotó Restaurante & Cachaçaria

(note: I took the photos marked with a * from wordpress user quebichomemordeu, and one or two are from websites (including the main Mocotó site) since mine didn’t turn out so great. If any of these are yours and you don’t want me using them, I’ll take them down.)

Palmito Pupunha

D.O.M. internship – week 1.

Palmito (or heart of palm) is somewhat of a staple vegetable in Brazil. It is widely used in salads and also in hot preparations such as savory pie filling, pizzas, stews, sauces, stir-fry — pretty much the possibilities are endless. Just the same as you can find anywhere else in the world, palmito is most commonly sold preserved with salt water in jars or cans. In such form they are pretty tasty straight out of the can. Palmito can be harvested from pretty much any palm tree. Most varieties of the palm tree die after the bud is cut for its inner core. Almost all types of palmito that were native to the coastal area that spans from the state of Bahia down to the east coast of Argentina became threatened with extinction due to over harvest in the wild. Brazilian authorities had to intervene making it illegal to harvest wild varieties (now only a few indigenous groups have permission to harvest following their ancestors’ sustainable methods). This change in policy made necessary for producers to invest in planting varieties that regenerate after being cut. The three types of palmito that are consumed the most come from the açaí, juçara, or pupunha palm tree. Açaí and pupunha are both native to the Amazon region.

Pupunha is increasing in popularity because it is a sustainable variety, meaning that when the stem is cut the root does not die and the plant can be cut again next season. According to EMBRAPA (the Brazilian’s government agricultural research department) additional advantages of pupunha is that the plant grows from seed to harvest-ready tree in only eighteen months. The palmito cut from pupunha is considered of superb taste and good size. In fact, the entire plant can be used but the most desired parts are the heart of palm and the fruit which is also called pupunha. EMBRAPA also mentions that pupunha is a crop that has little impact on the environment with a high yield per acre.

The cut is made on the upper part of the stem. Notice that each tree has several stems.

As my first station assignment inside D.O.M.’s prep kitchen I am working with garde manger chef Thiago Flores. One of the first tasks he showed me was how to process the raw pupunha segments. The raw pupunha palm is very perishable so it must be worked in a temperature controlled environment to avoid developing an acidic taste. To clean it, first you peel the outer part of the palm (what would be the bark on a regular tree) – this skin is removed and saved for garnish. Inside there is another layer that is too hard to eat so it is also peeled and discarded. Lastly, the top and bottom are trimmed by slicing a 1cm segment off from each end.

Chef Thiago Flores peeling palmito pupunha

Now the heart of palm is clean. For the specific preparation that was being made we trimmed the palmito, so it would fit through a mandolin. We used the mandolin to slice it in a fettuccine shape. This “pupunha fettuccine” is blanched and then sauteed with coral butter and served with glazed prawns. In addition to the prawns with fettuccine, pupunha is also used in other dishes at D.O.M.; there is a pupunha brandade served as a starter, another starter is pupunha carpaccio with scallops.

Thin sheets of raw pupunha carpaccio with marinated raw scallops and green pear.

The pupunha used at D.O.M. comes from São Cassiano, a farm located in Jaú in the state of São Paulo. According to their website the pupunha heart of palm is a low calorie food that is a good source of fiber and it is also rich in iron, potassium, zinc, and calcium. Palmito can also be used as a source of protein for vegetarian diets.

São Cassiano Pupunha

Jaboticaba

“A fruit is a vegetable with looks and money. Plus, if you let fruit rot, it turns into wine, something Brussels sprouts never do.”

-P. J. O’Rourke (1947 – )

On our way to DOM this morning, we discovered that every Thursday, the street is closed to traffic so that the neighborhood Farmer’s Market can take over. These markets are one of the things I’ve come to love most about São Paulo – every neighborhood has a farmer’s market at least one day of the week, so shopping locally is actually easier and more convenient than going to a grocery store. Markets are so important to the culture here that the days of the week – from Monday through Friday – all end in market. For example, Monday is Segunda-Feira, which literally means second market – the second day of the week, and a market day. We’re lucky to be staying near the Ceasa (the produce distribution center for the city), so we have local markets on Wednesdays and Saturdays.

Anyway, while browsing the produce on the way to work, a box of purple-black fruit that sort of looked like large grapes caught my eye. I pointed them out to Alex, who smiled and said “Oh… jaboticaba season is here…”

Jaboticaba

Jaboticaba – sometimes spelled Jabuticaba (I couldn’t find a source to say which was the correct spelling) is a fruit tree native to Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay, but it apparently originated in Minas Gerais, the same state pão de queijo is from. There are several species of jaboticaba trees, but the largest and most prominent here in Brazil is called the Sabara. The jaboticaba tree is an incredibly slow growing tree – it can take up to 40 YEARS to reach maturity and produce its first fruit. Because of this, it’s not widely farmed (a farmer would have to make a 40-year commitment before he’d see any return on his investment, after all), so almost all the jaboticaba in the markets come from private properties. It was introduced into California (in Santa Barbara) in 1904, but isn’t widely cultivated. It reaches a height of 10 – 15 feet in California and 12 – 45 feet in Brazil, depending on the species. The trees are profusely branched, beginning close to the ground and slanting upward and outward so that the dense, rounded crown may attain an ultimate spread as wide as it is tall. The thin, beige to reddish bark flakes off much like that of the guava. The jaboticaba makes an attractive landscape plant, and it’s considered by many to be a sign of luck if a jaboticaba grows in your land.

The name is derived from the Tupi word Jabuti (tortoise) + Caba (place), meaning the place where you find tortoises.

The tree may flower and fruit only once or twice a year (October and January-February being the largest harvests), but when continuously irrigated it flowers frequently, and fresh fruit can be available year round in tropical regions. The fruit is about 1-1.5″ in diameter and has a thick, purplish-black skin with a very gelatinous, white pulp. On our lunch break, we bought half of a kilo for a snack on the bus ride home. Eating them was bizarre to me – you’re supposed to squeeze them between your fingers until the pulp and seed pop into your mouth. I don’t know if I’m special or if I just haven’t done it enough before, but this resulted in a horrible mess with pulp flying everywhere and juice running down my hands and face (good thing the pulp is white, because I would have looked like a stained trainwreck by the time we finished the bag :p) . I figured out that if you bite the skin to puncture it, the pulp squeezes out a lot more cleanly and predictably, haha. The pulp contains from one to four small seeds (swallowing the seeds whole – also weird to me) and has a flavor that’s sort of similar to muscadine grapes – slightly sweet and low-acid. For a first-timer like myself, the texture of the pulp was the most memorable. You can’t really chew the pulp – you have to roll it around your mouth and savor the flavor before you swallow the pulp and the seeds. The skin is really tannic, and while it doesn’t exactly taste bad, I wouldn’t eat them on their own.

Health Benefits

After lunch, our bag of jaboticaba sparked a rather spirited discussion between our coworkers – they disagreed on whether jaboticaba “loosened you up” or “plugged you up”, per se. After doing some reading, I found out that many herbal doctors sun-dry the skins to make an astringent, which is used to treat hemoptysis, asthma, diarrhea, and gargled for chronic inflammation of the tonsils – so, to solve their debate, I guess it probably “plugs you up” if you eat enough of it. Several potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory anti-cancer compounds have been isolated from the fruit. Jaboticaba is rich in iron and contains calcium, phosphorous, and vitamin C, which make it good for building up resistance to infections. It also contains niacin and B vitamins, which, in addition to facilitating digestion and helping to eliminate toxins, can help prevent skin problems, rheumatism and hair loss.

Culinary Uses

The most popular way to eat jaboticaba is exactly as we did on the bus – just pop it into your mouth and swallow. It starts to ferment 3-4 days after it’s picked, so some use it to make jams, jellies, tarts, liqueurs, and strong wine. I’ve also seen it used in many of the ice cream shops here. Today at DOM, I tried their specialty jaboticaba-wasabi ice cream. It was surprisingly good – I can imagine it would be even better with other components.

It’s not widely cultivated in the US, but sources say you can find it once in a while in specialty markets in California, Florida, and Hawaii.

Jaboticaba Bonsai Tree

One last random fact that I discovered is that jaboticaba is gaining an increasing popularity in – of all things – bonsai. I have to say, the pictures were pretty cute, and the idea of having a mini jaboticaba tree when I eventually go back to the USA is somewhat appealing – I’m sure my cat would love it. =)

On Brazilian Desserts

“The proof of the pudding is in the eating.”

-Miguel de Cervantes, Spanish author, ‘Don Quixote de la Mancha’ (1547-1616)

Celebrating the holidays in the height of the South American summer has been bizarre for me in many ways, both culturally (monkeys with santa hats and palm trees? what?) and culinarily. I don’t want to be negative here, but – overall, I’ve been incredibly underimpressed by the desserts Brazil has to offer. There’s almost no lack of variety – or texture. Every restaurant pretty much serves the same three desserts : pudim (brazil’s version of Flan), a papaya cream topped with cassis, and some type of mousse, usually either chocolate or passionfruit. It’s all…spoonable, and it’s all sickeningly sweet. Maybe I was spoiled growing up with delicious fresh-baked cookies, cakes, and pastries – or maybe all the elaborate desserts the Baking and Pastry majors skillfully crafted at school set my expectations a little too high. I knew I wouldn’t have any of the familiar sights around for Christmas, but I guess I assumed I might have some of the familiar smells of baked goods.

Pudim

Pudim de Leite, Brazil's "flan"

By far, this is the most popular dessert item here. EVERY restaurant has their version of Pudim (pronounced poo-JEEN). Everyone loves it. Personally, I don’t particularly care for the texture – but for education’s sake, here’s the standard recipe, taken from Nestle:

- 1 can sweetened condensed milk

- 2 cans regular milk (fill up the empty condensed milk can twice)

- 3 eggs

- 1 cup sugar + 1/2 cup water for the caramel

1) Make the caramel – melt the sugar and water in a nonstick pan over low heat until it bubbles and caramelizes (don’t burn it or stir it). Pour the caramel into a bundt cake mold, coating the bottom and sides evenly. Let it cool.

2) Blend the milks and eggs in a blender until homogenous. Pour into the caramel-coated bundt cake pan.

3) Find a pot or pan that can hold the bundt cake mold and fill it halfway with water. Place the mold in the water bath, cover with foil (or a lid) and bake at 300ºF for 1 1/2 hours (or until a knife inserted into the pudim comes out clean).

4) Chill for at least 6-8 hours until fully solidified, then place a plate under the dish and flip it upside down to release the pudim. It should look something like the picture above.

Brigadeiro

Brigadeiro

Brigadeiro are almost never seen on restaurant menus, but every corner bakery displays these little candies – they’re the national candy of Brazil, and one of the only sweets I’ve actually liked here. Brigadeiro (Portuguese for Brigadier; known in some brazilian south states know as negrinho, literally “blackie”) is a simple Brazilian chocolate candy created in the 1940s, and named after the famous anti-Communist Brigadier Eduardo Gomes.

Because of World War II, traditional imports such as nuts and fruits were unavailable – however, Nestlé had just introduced its brand of chocolate powder and condensed milk in Braazil. It is believed that the creation and success of the candy was a combination of opportunities: the multinational corporation Nestlé, which introduced chocolate powder and condensed milk; the creators who named it after the famous politician, the need to find a replacement to imported sweets, and its ease of manufacture. Its shape is reminiscent of that of some varieties of chocolate truffles. It is very popular in Spain, Brazil, Chile, and Portugal. The candy is usually served at parties and is very popular among both children and adults.

It’s made by mixing sweetened condensed milk (1 can), butter (2 tablespoons) and cocoa powder (2 tablespoons, sifted) together. The mixture is then heated in a pan on the stove or in a microwave oven to obtain a smooth, sticky texture. If made on the stove, it’s ready when the mixture doesn’t stick to the bottom when the pan is tilted. The candy is then is to rolled into balls (butter your hands to make it easier) which are covered in chocolate sprinkles (that’s the way brigadeiros are served at children’s birthday parties – the adults just pour it into a cup and eat it with a spoon). Brigadeiro can also be used as a topping or filling for cakes, brownies and other pastries. When we did the catering for Peugeot a few weeks ago, we made little brigadeiro cups with Cocoa Krispies cereal on top – it was awesome. 🙂 Some bakeries also vary the recipe slightly by adding fruit purees instead of chocolate powder – it’s a base recipe that has infinite flavor possibilities.

Bolo de Cenoura vs. Carrot Cake

“Vegetables are a must on a diet. I suggest carrot cake, zucchini bread, and pumpkin pie.”

-Jim Davis, ‘Garfield’

When Alex’s brother said he was making a bolo de cenoura, I got excited – I have always loved carrot cake. I expected something like this:

American Carrot Cake

you know, raisins, nuts, grated carrots, cinnamon, and – the best part – cream cheese frosting.

Instead, this came out of the oven:

Brazilian Bolo de Cenoura

What? What is this homogenous orange mass, and WHERE is the cream cheese? <cue grumpy disappointed face>

After pondering over the intense orange color and the dripping chocolate covering, I decided to try it… and here’s where my adaptation skills came in. It was good… really good. However, it was absolutely nowhere near what I knew to be a carrot cake. If I looked at it, I started to miss the cream cheese… but when I closed my eyes, it was divine. It’s sweet enough to serve as a dessert, yet savory enough to serve at breakfast.

As usual, I decided to look into how this metamorphosis came to occur. According to Bo Friberg (“The Professional Pastry Chef”), the carrot cake originated some time during the Middle Ages, when sugar was a rare and luxurious treat. Carrots were often used in cakes and desserts due to their high sugar content. In Britain, carrot puddings began to appear in cookbooks in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and the use of carrots in desserts was revived in the United States during the 2nd World War, when sugar supplies were scarce.

Bo Friberg states that the carrot cake (with the characteristics of a modern cake) is definitely a North American invention. In this case, it would contain raw grated carrot, raisins, nuts and spices and traditionally would be filled and covered with a cream made with cream cheese base. (HA, I knew it!) The current carrot cake that Brazilians know gradually became adapted to the tastebuds of the country – which, after being here for a month, I can understand – heavy, overly sweet foods don’t really mix with the oppressive heat here.

I’ll leave you with two recipes – one for American carrot cake, and one for Brazilian Bolo de Cenoura.

American Carrot Cake with Cream Cheese Frosting

- 2 cups all-purpose flour

- 2 teaspoons baking powder

- 1/2 teaspoon baking soda

- 2 teaspoons ground cinnamon

- 1 teaspoon allspice

- 1/2 teaspoon nutmeg

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 4 eggs

- 1 1/4 cups vegetable oil

- 2 teaspoons vanilla extract

- 1 cup granulated sugar

- 3/4 cup brown sugar

- 1/2 cup honey

- 2.5 cups grated carrots

- 3/4 cup raisins

- 3/4 cup chopped pecans

Cream Cheese Frosting

- 1/2 cup softened (unsalted) butter

- 8 oz. cream cheese, softened

- 3.5 cups powdered sugar, sifted

- 2 teaspoons vanilla extract

Preheat oven to 350 degrees. Grease and flour two 8- or 9-inch round cake pans. Sift together the flour, baking powder, baking soda, cinnamon, allspice and salt. Set aside.

Beat the eggs, oil, sugars and honey and mix until well-blended. Fold in the flour mixture, carrots, raisins and nuts.

Bake for 40 minutes, or until the center of the cakes spring back when touched lightly. Cool in pans for 10 minutes; remove from pans to wire racks and cool completely.

For the frosting, beat everything together in a mixer until it’s creamy.

Brazilian Bolo de Cenoura com Cobertura de Chocolate

- 3 eggs

- 2 cups sugar

- 2 cups all-purpose flour

- 1 tablespoon baking powder

- 1 cup oil

- 3 large carrots, roughly chopped

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

For the Chocolate Topping:

- 1 can of sweetened condensed milk

- 1 cup of heavy cream

- 1 cup of cocoa powder, sifted

Preheat oven to 350 degrees Fahrenheit. Grease and flour a 9×13 pan. Put the eggs, chopped carrots, oil, and salt in a blender. Mix on high until homogenous.

In a separate bowl, sift together the sugar, baking powder, and salt. Combine the blended mixture with the dry ingredients in the bowl, being careful to not over-mix.

Bake until a toothpick comes out clean in the center – the recipe doesn’t specify how long, but I’d check it after 25 minutes or so.

For the frosting, mix the condensed milk, cream, and cocoa powder together in a pan. Stir constantly over a medium-low flame until it becomes a creamy, frosting-like consistency.

As usual, if you try either recipe, please comment and let us know how it turned out!